We’re all a little autistic…and other mistruths

Some three years ago, I responded to a recruitment call from an organisation called Connections in Mind (CiM), who were looking for executive function1 coaches. CiM specialises in raising awareness and understanding of neurodiversity and the impact of living with neurodivergent conditions, as well as coaching neurodivergent children and adults to develop their executive function skills – and, more broadly, perform to their full potential.

Since taking on that executive function coaching work with CiM, I’ve had the opportunity to work closely with numerous neurodivergent clients, supporting them in dealing with the daily challenges brought about by living in a world that is, more often than not, stacked against them. As a mother to an incredible son with ADHD, and as a partner to a brilliant autistic man who also has ADHD, I’ve also seen those challenges through a very personal lens.

It occurred to me that although this work is hugely important to me I haven’t written anything about any of it. So I thought I would start with something that often comes up when I have conversations about this – the idea that ‘we’re all a little autistic’ or that ‘everyone is on the spectrum somewhere’.

What actually is the autistic spectrum?

I think that this perspective has its roots in a misunderstanding of what the autistic spectrum actually is.

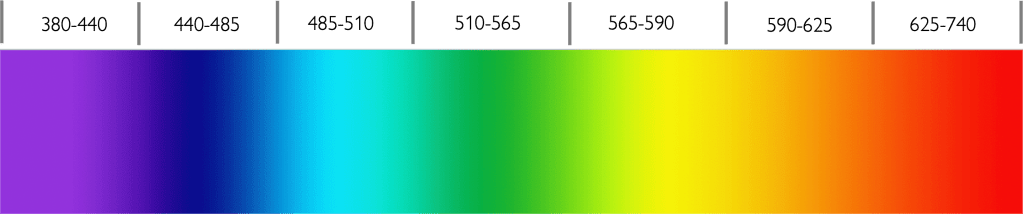

I’ve seen comparisons made to the visible light spectrum and I think it’s a useful analogy that I’m going to reproduce here. So this is a representation of the visible light spectrum – the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that’s visible to the human eye. As wavelength gradually increases, we move from violet to red:

We can describe each colour on the spectrum in terms of gradients or intensities. Red, for example, can range from pale to quite intense. We don’t, however, compare colours in terms of how far along the spectrum they are, or how they are positioned relative to either end of the spectrum. Violet isn’t ‘not very red’, and green isn’t ‘middle-of-the-road red’, and red isn’t ‘acutely red’, or somehow ‘more on the spectrum’ than violet is:

What I often encounter is a perspective of the autistic spectrum that looks like this:

I’ll put aside the problematic nature of functioning labels2 for now (if you’re interested in this, have a look at the footnote) to make the point that we tend to think of spectrums in terms of linear progressions, and so the conversation around autism is often how someone is autistic to a less problematic (to other people) or somehow more drastic/severe/tragic extent.

What does this tell us? When people talk about someone being ‘more’ or ‘less’ autistic and ‘everyone being on the spectrum somewhere’, it seems to me that they’re thinking about a question of gradient, like we were all varying intensities of red. Like any two neurotypical people, no two autistic individuals are identical, and the idea that you can position them all along a scale of increasing degrees of autism is damaging, because it diminishes people to reductionist stereotypes.

In fact, it’s also fundamentally incorrect, because you can’t be ‘a little bit autistic’ or ‘very autistic’ in the same way that a colour can be intensely red or pale red. It would be like saying someone was ‘a little rainbowy’ when they were only wearing blue and red.

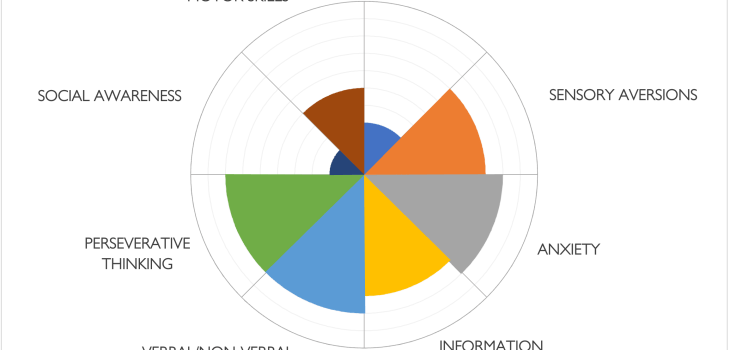

This is because the autistic spectrum is not a linear spectrum. I’m going to illustrate this point with the autism wheel or pie chart, which I think presents a much more accurate portrayal of the diversity of experience within autism and gives us a helpful visual representation of what the autistic spectrum really looks like.

The autism wheel, or autism pie chart

The illustrative examples above show us how autism might manifest very differently in two autistic individuals. In the two contrasting charts, you’ll see how individual autism traits are represented by separate wedges of the pie. (In these examples it’s important to note that the pie chart represents a simplified picture of autism and does not include every relevant trait.)

Challenges in multiple areas across the autistic spectrum

The first crucial observation to make is that all autistic people are affected in one way or another in most or all of the individual traits represented in each chart above. Neurotypical people may well have challenges in one or two of these areas, but in order for someone to be considered autistic, they must have difficulties in multiple categories across the autistic spectrum. If you only have a slice of the pie – if you only have difficulties in a couple of these areas – then you aren’t ‘a bit autistic’, although you may well be neurodivergent in another way. For example, if you have significant issues with only sensory processing, you might have sensory processing disorder. Or if you struggle with certain executive functions such as self-control and the ability to focus attention and task-switch, allied with social awareness challenges, you might have ADHD.

The uneven cognitive profile and the problem with making assumptions

The autism wheel/pie chart also provides a clear visual representation of one of the distinguishing features of autism that is described in the DSM as an ‘uneven profile of abilities’, or an ‘uneven cognitive profile’. This basically describes how someone on the spectrum may have significant strengths in one area, but be severely lacking in another. Taking the left profile above, one example might be someone with very high verbal and academic ability, who also struggles with social awareness, high anxiety and perseverative thinking – becoming very fixated on particular thoughts or tasks and being unable to redirect their attention to other things. To much of the external world they may be mildly affected by their autism. In reality, however, they may have hugely disabling executive dysfunction that has a significant impact on their employment prospects and relationships.

In contrast, the right profile might represent someone who more closely fits the stereotypical ‘severely autistic’ profile – mostly non-verbal, with neuro-motor differences and high repetitive behaviours. Yet that individual may have much higher social awareness and information processing capacity than might be perceived.

Being aware of this uneven profile is important because we often make assumptions about a person’s overall ability and capacity when looking at a slice of their strengths or challenges. As Bradshaw, et al. (2021), for example, note: “Using functioning labels and autism levels overlooks the real challenges and barriers of autistic people who may not outwardly appear different, and minimises the strengths, abilities, and capacities of those who do.”

Neither of the individuals above is ‘more’ autistic than the other. Autism comes in all shapes and sizes, and each individual’s experience of autism is uniquely their own. That experience can also change and develop over time, and the autism wheel or pie chart also acknowledges and accommodates the possibility of that fluid development.

In writing about this I’ve been reminded that there is so much that I have learnt over the past few years not only about neurodivergence itself, but also about my own attitudes and biases with regard to performance, resilience and patience. However, I’ve also learnt about how much I still don’t know, and that although general awareness and understanding of neurodivergence has come so far in recent years, we still have a long way to go to shape a world that is genuinely neuroinclusive.

I hope that you will take two things away from this brief article. The first thing is that, in future conversations, you too will have the ability to correct the misapprehension that ‘we’re all on the spectrum somewhere’. Although I think it’s important to recognise that people may have good intent when they say this, the real impact of loose identification like this is that it can be very hurtful and disheartening for autistic people as it diminishes their lived experience.

I also hope that I, as much as you, remember to continually question the assumptions that we may be making about our autistic family members, friends and colleagues. Dr Stephen Shore, an autistic professor of special education at Adelphi University and an advocate for autism awareness, says that “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.” Like any other person, autistic people are individuals with unlimited potential, and we need not to measure people on the basis of what may be visible.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts – drop me a comment or message and let’s start a conversation.

Natalie Snodgrass

– Quiet Space Ltd

Footnotes

- Executive functions (EFs) are the high-level cognitive functions that enable us to successfully undertake tasks such as planning and scheduling our time, focusing our attention, remembering instructions, regulating our emotions, and keeping going in the face of challenge. Moderated primarily by the frontal lobe in our brains (specifically the prefrontal cortex), the core EFs relate to three types of brain function: working memory, self-control, and mental flexibility. Whilst we all have difficulties with executive functioning from time to time, neurodivergent brains can often experience particular EF challenges. In EF-focused coaching, we help people to build skills and strategies to improve their executive functioning, which strengthens the foundations upon which they are then able to build the lives they want to lead.

- ‘High-functioning autism’ is an unofficial term often used for individuals with autism spectrum disorder without an intellectual disability (Alvares et al, 2020) – in other words, whose autism symptoms may appear mild to the outside world. This term is not used in official diagnostic criteria, set out in diagnostic manuals such as the ICD-11 and DSM-5 (the International Classification of Diseases and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). The DSM-5, for example, categorises autism in terms of the severity of the condition and how much support a person requires in daily life. Level 3 (requiring very substantial support) includes those who may have significant learning difficulties, Level 2 (requiring substantial support) includes people who would struggle to live independently, and Level 1 (requiring support) includes people without intellectual disabilities who have the capacity to live independent lives. ‘High-functioning autism’ often gets used interchangeably with Level 1 in this respect.

Functioning labels are problematic because how well someone functions can actually fluctuate significantly on a day-to-day basis. And even though the diagnostic categorisation has moved away from functioning labels, I have to confess that I still find autism categories problematic, because it is small comfort to know that you are either ‘high-functioning’ or require little support on a day when your anxiety and sensory over-stimulation is so intense that the only way you can cope is by hiding from everything. People can also be high-functioning in some areas while having significant difficulties in other areas (a distinguishing feature of autism – what’s described as an ‘uneven cognitive profile’). And despite other common misconceptions, ‘high’ function doesn’t necessarily equate with an absence of learning difficulty, nor ‘low’ function with being non-verbal.

References

Alvares, G. A., Bebbington, K., Cleary, D., Evans, K., Glasson, E. J., Maybery, M. T., Pillar, S., Uljarević, M., Varcin, K., Wray, J., & Whitehouse, A. J. (2020). The misnomer of ‘high functioning autism’: Intelligence is an imprecise predictor of functional abilities at diagnosis. Autism, 24(1), 221–232.

Bradshaw, P., Pickett, C., Brooker, K., Urbanowicz, A. & van Driel, M. (2021). ‘Autistic’ or ‘with autism’? Why the way general practitioners view and talk about autism matters. Australian Journal of General Practice, 50, 104-108.

1 COMMENT

[…] weaknesses – the ‘uneven cognitive profile’ or ‘spiky profile’ that I talked about in my last article on the autism spectrum, describing how autistic people (and neurodivergent people more […]