Articles

Articles

Neurodiversity and neuroinclusion: embedding difference as standard

1. Introduction

This article was inspired by one of my neurodiversity and executive function coaching clients, whom I’ve been working with for several months now through the government’s Access to Work1 scheme. D was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) as an adult, with co-occurring Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD)2.

At a recent session we celebrated a major milestone that shouldn’t have warranted being either a celebration or a milestone. D, after two long years, had finally received approval from her employer. For what, you ask? For the purchase of a non-standard work laptop with customised setup and specialist programmes, which would allow her to undertake her job duties much more efficiently and effectively.

D struggles particularly with making presentations and fielding questions in the moment due to her RSD and the working memory challenges of ADHD, but when she’s made reasonable adjustment requests for questions to be submitted in advance for an important presentation that she’s also circulated a paper for in advance, this hasn’t been taken seriously because it isn’t a problem for anyone else and no one has made the time to read her paper before the meeting anyway.

D is also having to secure her own funding in order to make sure that her manager and colleagues receive ADHD awareness training, and has to constantly self-advocate and push for change in the face of dismissive attitudes and workplace practices that are not effective for anyone, let alone neurodivergent people. We spent that session working to develop D’s disability passport3, and got into a discussion around neuroinclusion, the social model of disability, and what constitutes a ‘reasonable adjustment’ for disability vis-à-vis what is simply good workplace practice.

2. Neurodiversity, neurodivergence, neuroinclusion: What does it all mean?

The language we use matters – it shapes how we see the world and one another, guides our behaviours, and reflects our values, beliefs and assumptions. So before I go any further, I think it’s worth briefly explaining what I mean when I talk about neurodiversity, neurodivergence and neuroinclusion, recognising that not everyone may have the same language preferences or make the same linguistic distinctions.

Neurodiversity

When I speak about neurodiversity4, I’m referring to what are naturally occurring differences in human neurocognition. This is the idea that normal, natural human variation accounts for not just neurological differences such as autism or ADHD, but also simply the fact that no two brains function exactly alike. Neurodiversity, in other words, is standard: we are all part of a complex neurodiverse species. Each of our brains is unique, shaped by genetic factors as well as by each of our backgrounds, cultures and life experiences. The neurodiversity movement, a social justice movement that emerged during the 1990s, campaigns for the rights, equality, respect and full societal inclusion of all neurological differences, while increasing the acceptance and inclusion of all people.

Neurodivergence

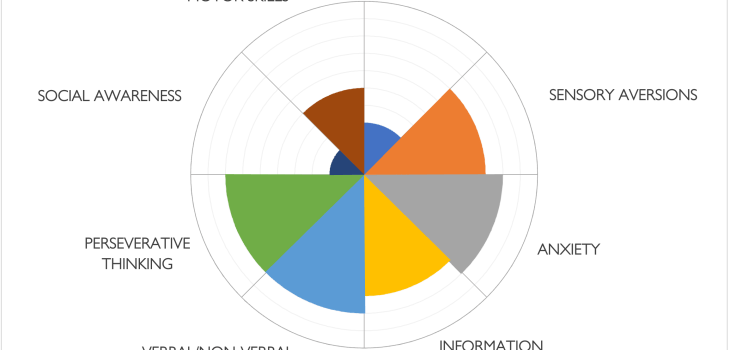

Within that neurodiversity, most people have neurotypical brains. Others have less typical neurotypes – neurodivergent brains with pronounced strengths and weaknesses – the ‘uneven cognitive profile’ or ‘spiky profile’ that I talked about in my last article on the autism spectrum, describing how autistic people (and neurodivergent people more broadly) may have significant strengths in one area, but be severely lacking in another. Collectively we might also refer to neurominorities.

At an individual level, people may relate to different terms and have preferences for how they want to refer to their diagnosis conditions. They may, for example, identify as neurodistinct or neurodifferent rather than neurodivergent, given that ‘divergence’ from the standard isn’t necessarily neutral and can still feel loaded with judgment. Or sometimes ‘neurospicy’, which still makes me smile whenever I come across it. Or they may avoid the overarching terms altogether and prefer to identify with their specific condition, e.g. “I’m autistic/dyslexic/I have ADHD”.

Neuroinclusion

What, then, about neuroinclusion, and where it sits under the broader umbrella of equality, diversity, inclusion and belonging? When I talk about neuroinclusion, I’m referring to recognising, respecting and creating a level playing field for neurocognitive differences in exactly the same way as we strive to do with differences in race, religion, sex and gender and all other human variations. Neuroinclusion is about embedding difference as standard.

3. Challenging our biases: neurodivergent strengths, the social model of disability, and the neurodivergent lived experience

I think that the first thing we need to do is stand back and challenge our perceptions, filters and biases. The 2020 Institute of Leadership research report “Workplace Neurodiversity: The Power of Difference” revealed that 50% out of 1,156 UK employers admitted that they would not employ a neurodivergent person (with the highest level of bias existing towards Tourette’s and ADHD). Survey outcomes also showed a significant lack of understanding and awareness about neurodiversity, despite an estimated 1 in 7 of the population being neurodivergent.

A couple of quotes from the report that stuck with me:

“It is a common misconception that people having one of these conditions (…) are less intelligent and less able, whereas in fact there is no association between intelligence and neurodiversity.”

“Most employers are scared to hire neurodiverse people as they only calculate the risks based on the deficits of the condition.” – Claire Smith, CEO, Autistic Nottingham

So far, so disheartening.

Neurodivergent strengths

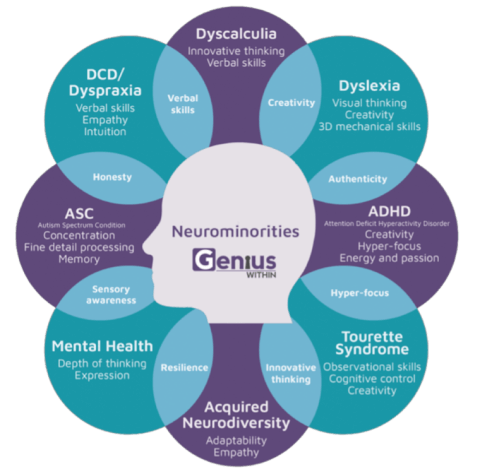

So let’s swap over that negative filter and instead look at the diagram below from Dr Nancy Doyle, which gives a great, simplified overview of the overlapping strengths of different neurodivergent conditions. The diagram includes diagnoses that tend to be more commonly encountered (if not necessarily commonly understood) such as autism and ADHD, but also, for example, the recognition that anyone who may have been neurotypical by birth can become part of the neurodivergent community later in life, through acquired brain injury.

One of the neurodiversity movement’s main goals is to shine a light on the benefits of this diversity. For example, my autistic or ADHD coaching clients may have sought support to deal with executive functioning challenges, but we aim to work together in a way that seeks to productively channel and build on their vibrant creativity; passion; ability to hyper-focus; complex problem-solving abilities; or novel, unusual insights and perspectives.

Society disables people, they’re not necessarily disabled: the social model of disability

Neurodistinct people are differently abled because of underlying differences in neurocognitive function that can lead to various impairments. The main issue is not in the impairments themselves, but what arises when we don’t account for those impairments. This is the perspective of the social model of disability, which frames disability as predominantly a social construct in which attitudes, practices and structures create limits on individuals’ functioning, and put barriers in the way of them reaching their valued goals.

What often happens, even in organisations that on paper have the right policies and procedures in place, is that neurodivergent people have to fight for access to the adjustments or considerations that would make it easier for them to engage and manage at work. Apart from D, some other real-life examples I’ve seen have included the “If I make this allowance for you I’ll have to make it for everyone” argument around headphones in the office to help with focus; insisting that someone stay at their desk to work rather than having autonomy to go for a walk to think through a data problem; refusing a request for a desk located in a quieter and more enclosed corner of an open-plan office to manage sensory overstimulation; and a three-line whip for compulsory team bonding activities.

In other words, even if we recognise and hire for strengths, we don’t consistently and proactively support to level the playing field for impairments. Instead, we refuse to trust our talented people, and place the burden right back on the individual to have to self-advocate and negotiate daily hurdles just to be able to do their jobs.

Daily living for many neurodivergent people is often invisibly tough. Neurodivergent populations are significantly more likely to be exposed to trauma and adversity across the lifespan. Many struggle with mental and even physical ill health from the imprint of childhood traumas, as well as an increased likelihood of experiencing further trauma as an adult through the impact of workplace bullying, discrimination, and feeling misunderstood, unheard, and unseen. It’s unsurprising that, for those whose neurodivergence can be concealed, it often is: in order to fit in, rather than cope with the cost of being different. And so not only is support not requested, but disclosure not made due to self-protection – at great private and personal cost.

If we were really committed to truly neuroinclusive ways of working, disability would not have to be the inevitable outcome for many neurodivergent individuals.

“Impairment is a fact of life, but disability is a social and cultural artifact” – Professor Tom Shakespeare, Royal Institution of Great Britain talk (YouTube link)

The social model of disability stands in stark difference to what is still the norm – the medical model, which says that people are disabled because of their impairments or differences.

The difference is important. The medical model drives us towards an impairment-focused conversation in which neurodivergent people need to be modified or accommodated so that they can fit within neurotypical designs and standards. It also drives the focus towards legislative and policy frameworks, checklists for what workplaces need to do to meet their obligations, and concerns over what managers ‘can and can’t say’ in order to be compliant. ‘Disability’ in this context can become a dirty word.

Understanding the neurodivergent lived experience: examining our assumptions and revising our models

The experience of D, whom I mentioned at the start of this article, is not unusual. The sad thing is that her workplace is, actually, relatively progressive in its attitude towards neurodivergence.

As we’ve seen, a lot of that attitude is bound up in lack of knowledge, partial information and misunderstanding. It’s also rooted in a lack of motivation to step back and rethink the things that ‘we’ve always done this way’, because ‘we’ aren’t the ones on the burning platform and don’t personally experience the need for change. Part of the difficulty here stems from the fact that neurodivergent traits may look eccentric and can even seem to conflict with what workplaces usually associate with professional competence, such as social and political awareness, tact and diplomacy, productivity and good timekeeping, and being a ‘team player’ who doesn’t require any particular managerial attention.

This, however, doesn’t mean that neurodivergent people aren’t good employees. It means that our notions and standards for what constitutes a good employee need to shift, adapt and expand; that we need to examine our damaging assumptions and stereotypes; and that we need to create supportive conditions not just for neurotypical performance but also neurodivergent excellence.

For example, many autistic people’s communication can come across as very direct, often blunt, which can jar with a mode of communication that is used to greater subtlety. One potential downside of greater subtlety, however, is that one of its common bedfellows is not actually saying what you mean. Thus the neurotypical ear is trained not to take what it sees on face value, and tends to search between the lines for what may have been implied, omitted or disguised. In unhealthy workplace cultures, this creates a constant wariness in employees who are concerned or suspicious about what their colleagues aren’t telling them. This is the beauty of direct and honest communication, and many autistic people have it in spades. It is straightforward and unambiguous, there is no game-playing, and everyone knows where they stand. This is not to say, of course, that better communication skills don’t need to be cultivated. But the learnings are for both neurotypical and neurodivergent people alike.

Another example that comes up frequently in my coaching work is the strong sense of justice that many neurodivergent people experience. This can emerge as an intense need to speak up and persist when others remain silent in the face of unfairness or a violation of rights and principles, which can often lead to being labelled as a ‘troublemaker’. When we take a step back to look at what’s really going on here, we may realise that the real challenge might be a workplace without a healthy level of psychological safety (more on this below) in which honest opinions and feedback can be discussed without threat of recrimination, blame or punishment.

There is a valuable opportunity here for a curious, empathic dialogue that has compassionate humanity at its core, seeks first to understand, and is committed to finding ways to genuinely live out what it means to be inclusive.

4. A vision for neuroinclusion

Neuroinclusion benefits everyone: think of inclusion by design

I want to start with the core premise that, just as difference is standard, neuroinclusion benefits everyone.When we remove barriers for a few, we can increase accessibility for all. Through this we can begin to do some important reframing: from adjustments and accommodations being ‘special treatment’ or even an inconvenience, into an opportunity for us to create the conditions for high performance for all our people.

The principles of neuroinclusion by design – thinking about the needs and abilities of your neurodivergent employees when creating spaces, systems, processes and practices – are pretty aligned with Universal Design, which is the design of buildings, systems, environments etc. so that they can be accessed, understood and used to the greatest extent possible by people regardless of age, disability or other factors. This is not a special requirement, for minority benefit, but is in fact a fundamental condition of good design.

This can happen at the most basic of levels, like with D. One of the requests on her disability passport was for the introduction of written agendas, to be circulated in advance of scheduled meetings to support preparation and a clear, predictable flow of discussion. What in some organisations is already standard administrative practice is still a ‘reasonable adjustment’ request elsewere, but this also gives us the precedent and model for changing our thinking.

Recruitment is a great area of focus for organisations looking to embed inclusive design in their processes. Many tweaks can benefit all candidates, not just neurodivergent ones, and allow them to show up at their best. Some quick and no-cost options include thinking about the detail and structure of the information that’s issued to candidates pre-interview – clear timings and venue information, details of who will meet candidates on arrival and who will be on the panel, and clarity on how the interview will be structured. Providing a hard copy of questions at or just in advance of the interview can serve as an important aide memoire not just for candidates with working memory challenges, but also all candidates who can get anxious and overwhelmed under the interview spotlight.

Psychological safety: create a high-performance environment where all people feel safe to show up fully and authentically

Psychological safety is present when colleagues trust and respect each other and can speak up with candour, airing their ideas, questions and concerns and making mistakes, without fear of humiliation or retribution. It’s a shared belief, held by members of a team, that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking. First conceptualised in the 1990s by Professor Amy Edmondson from Harvard5, over 20 years of research have since identified psychological safety as the #1 top differentiating factor in what makes a high-performance team, and a pivotal factor in increasing collaboration and innovation.

When I think about inclusion, I have often concluded that we limit ourselves because we spend lots of time focusing on our frameworks, charters, policies, processes, etc., but then stop short of what happens in the small spaces: the quality of our human interactions.

How do we create thoughtful spaces for conversation where all of us feel safe not only to show up as we are, but also to take up our rightful space and use our voice? This is the practice of creating psychological safety. Showing up in this way takes vulnerability, and all the more so if you’re neurodivergent. We don’t see the additional cognitive load it’s taking an autistic colleague to work out unspoken social group norms, or how someone with auditory processing disorder may need additional time to process what’s been said before they can think about a response, or when we lose valuable contributions from neurodivergent or socially anxious colleagues who have difficulties in navigating group discussions and so, feeling unsafe, choose to stay silent. When we create spaces in which people feel safe to be vulnerable, we create spaces in which people can be at their best.

Give your managers licence to operate, with clear guidance around adjustments to individual work contexts

In several unrelated conversations last year with various senior university leaders I was interested to hear the same question popping up: how do we get people to move away from a culture of permission seeking? We keep telling them to take risks and they don’t!

There is a clear link here to psychological safety – and what happens when you don’t have it. In an organisational culture where there is fear around the consequences of taking risks, you can’t simply tell people to take risks. Rather, you have to not only actively model risk-taking, but also systematically reframe and destigmatise failure; invite participation; set up structures and processes to build people’s confidence that voice is welcome; express appreciation; and regularly refresh your orientation towards continuous learning. This is the same kind of environment that invites and nurtures inclusion.

Within permission-seeking and risk-averse cultures, requests for reasonable adjustments often get framed as issues that need solving. They also tend to create bureaucratic delays through unnecessary layers of approval. Giving managers greater licence to operate, with greater autonomy over their staff budgets, can make the process of making reasonable adjustments an integral and value-added part of boosting staff performance. It’s worth making the observation that many adjustments can be undertaken at negligible to relatively low cost, and that ‘fair’ doesn’t mean treating everyone in the same way.

An important observation worth reflecting on, if you’re a manager yourself, is how you can be proactive about supporting your neurodivergent team members. Asking for adjustments can be difficult not necessarily because of the request itself, but because it’s not always clear what to ask for or what would help. Organisations can support this through developing resources noting the different adjustments that may have been made in the past and what options there might be, which can be a helpful springboard for discussion.

Educate staff and encourage allyship within your organisation

We all have biases, blind spots and imperfect knowledge, and we have a natural tendency to gravitate towards and favour people who are similar to us. In a neurotypical world, our neurodivergent colleagues can, through no fault of their own, be subconsciously judged and left on the outside.

Changing this requires awareness-raising and education – we cannot challenge our own biases until we are aware of them and have the language to talk about them. Neurodiversity awareness training and education through e-learning, webinars and toolkits, provided by specialist psychological consultancies like Lexxic, are great ways to reach large numbers of staff and start conversations about neurodiversity in your organisation.

You can also make an impact as an individual through becoming an ally. As an ally, you might not be neurodivergent yourself, but you can support and take action to help your neurodivergent peers. There are a number of ways in which you can do this:

- Listen to your neurodivergent colleagues, learn from their lived experiences, and actively educate others.

- Speak out if you see discrimination happening.

- Volunteer to act as an inclusion ambassador, dignity at work contact, or other similar roles within your organisation, or get involved with any relevant employee resource groups (ERGs).

5. Neuroinclusion is a shared responsibility

Neuroinclusion isn’t someone else’s responsibility. We all need to play a part, and we can make a big impact even in the everyday gestures. It does mean that we have to look at and do things differently from how we may have been used to in the past, but this is the essence of inclusion – that we all take our share of the heavy lifting in making this world a fairer place.

Natalie Snodgrass

– Quiet Space Ltd

- Access to Work (AtW) is a government grant that funds practical support if you have a disability, health or mental health condition. Your disability or health condition must affect your ability to do a job on a day-to-day basis or mean you have to pay work-related costs, and the funding can support a wide range of support such as a support worker or coach, specialised equipment, travel fares to work if you can’t use public transport, and disability awareness training for your colleagues. The grant does not have to be repaid.

The aim of the scheme is to help you start work, stay in work, be able to move into self-employment or start a business. To be eligible you have to be over 16, self-employed or either in a paid job or about to start a job or work trial with an employer based in England, Scotland and Wales (there’s a different system in Northern Ireland). Full details are available on the AtW website. ↩︎ - See this Additude Mag link for some info about RSD. ↩︎

- Disability or reasonable adjustment passports (also known as workplace adjustment passports) were introduced following a GMB motion at the TUC’s Disabled Workers Conference in 2018. They provide a continuous, portable record of an individual’s agreed workplace adjustments that can be transferred when the individual changes roles or managers, avoiding the need for the adjustments to be re-explained and re-negotiated. Further information is available here from the TUC. ↩︎

- Judy Singer (Amazon link to updated reprint of Singer’s original 1998 thesis “Neurodiversity: The Birth of an Idea”), an Australian sociologist, coined the term ‘neurodiversity’ as one of the seminal ideas in her pioneering work that mapped out the emergence of what was, at the time, a new category of disability with no name. ↩︎

- Professor Edmondson’s profile at Harvard Business School. ↩︎

I posted the image above on my social media accounts a while ago and was amazed to find how much it resonated with people. Maybe you’re not tired, maybe you’re just doing too little of what makes you come alive. It’s a theme that has kept cropping up in my coaching sessions and in random conversations with people over these last couple of months, as well as something that has been particularly close to my heart this past year.

I posted the image above on my social media accounts a while ago and was amazed to find how much it resonated with people. Maybe you’re not tired, maybe you’re just doing too little of what makes you come alive. It’s a theme that has kept cropping up in my coaching sessions and in random conversations with people over these last couple of months, as well as something that has been particularly close to my heart this past year.