Articles

Articles

Leadership: laying the groundwork for psychological safety

In a coaching conversation last week, the subject of sticking your head over the parapet came up. Tina, as we’ll call her, is driven by an incredibly strong sense of natural justice, and is also a highly creative leader drawn towards doing things differently. Although she isn’t naturally assertive, she believes it is her responsibility to role-model the act of speaking up, and she’s cultivated this over time.

Unfortunately, Tina is not supported organisationally by a climate that welcomes her speaking up, so she’s doing it in the face of defensiveness and opposition from senior leadership. Her experience of the culture in her department and more broadly her organisation (a UK university) is that, despite having all the ‘right’ policies, ultimately it closes ranks and preserves what is often an exclusionary status quo. Understandably, she’s frustrated, particularly because in previous organisational environments her experience was of staff feeling safe to have open, honest conversations; having licence to experiment with new ideas; and having the space and safety to fail intelligently, without an accompanying blame culture. Tina feels that her performance and career is being compromised because of this.

Because Tina has seen first-hand the direct benefits of psychological safety to both individuals and their organisations, she wants to take agency in establishing this where she can, starting with the conditions that she is co-creating not just with her local team but also in terms of the climate of all the spaces where she shows up at work.

What is psychological safety?

If you’re not already familiar with the concept of psychological safety, here’s a short and important primer, because the term can get an undeserved bad rap for being too lightweight, usually due to being misinterpreted as being politically correct or ‘nice’.

What do we mean when we talk about psychological safety? Professor Amy Edmondson, from Harvard Business School, first identified the concept of psychological safety in work teams in 1999, and over 20 years of research now demonstrates that organisations with higher levels of psychological safety perform better on almost any metric or KPI.

Edmondson defines psychological safety as “a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns or mistakes.” It’s about creating an environment in which everyone’s voice can be heard, where people feel included and appreciated, and in which everyone has a felt sense of safety: safe to speak up, share ideas, not know things, admit mistakes and fail intelligently (recognising that this is a crucial factor for creativity and innovation). This safety and space are fundamental to high performance, collaboration, staff wellbeing, and transformational and sustainable organisational change.

It isn’t necessarily comfortable, because psychological safety doesn’t shy away from appropriate challenge – but leaning into productive conflict is far preferable to false harmony. When we feel safe at work, we can bring our best and be at our best. We can tackle the tough stuff and the difficult conversations being able to say what needs to be said, while continuing to nurture valuable working relationships. And it’s evidence-backed: Research has identified psychological safety as the #1 differentiating factor for high performance teams and a pivotal factor in increasing collaboration and innovation. We can measure it (through the Fearless Organization Scan), and as the saying goes: what gets measured gets improved.

Whose responsibility is it to create psychological safety?

In my leadership coaching, I’ve had a lot of conversations with people who can theoretically see the benefits of psychological safety, but don’t know how they can individually make a difference, particularly when they already feel disempowered by organisational cultures and toxic senior leadership behaviours.

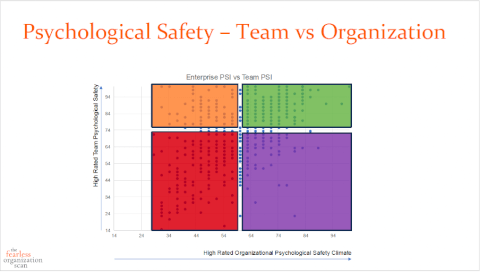

The question I am often asked is this: Can you have psychological safety in an organisation if there is no awareness, appetite or vision for this from the top (at least not yet)? The answer is yes. You may find the snapshot below interesting in this regard, which shows team vs. organisational psychological safety ratings as measured by global research undertaken by The Fearless Organization. The data reflects how very highly-rated teams can be located within organisations rated as having a poor psychological safety climate. The reverse, however, is not the case; there is not a single datapoint for a low-rated team within a great organisation.1

In essence, psychological safety grows: from pockets in teams, to pools in departments, you can have influence and build a safer climate from the ground up.

Crucially, this also reflects how psychological safety attunes to a distributed or collective leadership model – what this means is that although top-down leadership visibly sets the tone, role-models constructive behaviours and charts the direction for the kind of culture that a team or indeed organisation wants to stand for, all members of the system have a role to play.

And because psychological safety is co-constructed, this means that leaders at all levels of the organisation have agency. Whether you’re in a formal leadership role or not, you can learn skills and adopt practices that support the creation of psychologically safe spaces around you.

Leadership skills and practices that support psychological safety

So I thought I’d outline a few personal thoughts on some key leadership practices and competencies that support the development of psychological safety. It may be helpful to observe that, in all probability, much of this will not be in fact separate from what you are already doing, or what is already happening within your organisation. In this respect the intentional practice of psychological safety is wholly compatible with existing management approaches, leadership methodologies and inclusion practices. I hope that these will serve as some useful prompts for reflection, whether you’re thinking about this from your own individual perspective or have an organisational hat on.

The leader as coach

There are a huge number of leadership styles that are talked about in the literature, and effective leadership is very much about being well-versed in multiple styles, as well as the ability to flex between them dependent on the needs of the situation. There is one particular leadership style, however, that I think is especially aligned with development of psychological safety in teams, and that’s a coaching style of leadership. This is all about building long-term capability in your team, through understanding their strengths and weaknesses and facilitating their development, and non-judgmentally supporting them to find the answers for themselves rather than dictating how things should be done.

The effective leader-coach supports the development of psychological safety in their teams in several ways. Their focus on understanding and developing their team is not only a vital complement to the climate of empowerment and innovation that marks out high-performing teams, but also allows them to build the strong trust with their team members that is a vital foundational component of psychological safety.2

Your attitude to, and skill at dealing with, conflict

We all have different tolerances and attitudes towards conflict, starting with whether we see conflict as a healthy thing or not. Many of us equate conflict with confrontation, and instinctively avoid any prospect of it by not talking about things that should be talked about, preserving a false harmony that stores up problems for the longer term. Many of us don’t have effective tools for effectively resolving conflict when we find ourselves in it – instead we experience defensiveness, aggressiveness, blame and capitulation.

Conflict can be productive, however – and you actually want productive conflict on your team, as part of an ability to enter into open, honest conversations. When team members can address problems directly and productively, explore different opinions with curiosity, and thoughtfully disagree with mutual respect, it’s an indicator of high psychological safety, and it boosts the team’s ability to problem-solve and innovate.

At the heart of productive conflict is the understanding that we all experience reality in different ways – as Anaïs Nin said, “We do not see things as they are. We see things as we are.” The key to better working relationships is listening to understand so that we can expand our perspective and learn to hold the space for multiple realities.

As a leader, understanding your attitude towards conflict and learning about different conflict management styles can be incredibly rewarding not just for your personal development but also in the interests of more effective communication with your team. Working not just on your conflict management skills, but also on how to facilitate genuine dialogue (as distinct from debate or discussion), and on building the insight required to ‘read the room’ – the system of structural dynamics – can help you to improve the way that your team talks, so that conversations which need to take place can happen constructively in the room, rather than being held back.

Designing from the margins: are your practices inclusive and affirming?

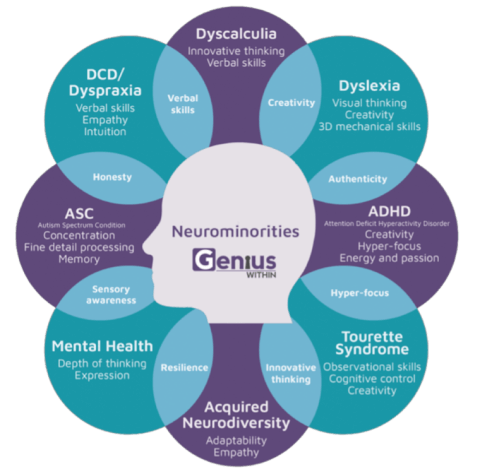

In my last article on neuroinclusion, I wrote about how no two brains are identical, how neurodiversity therefore describes the human condition, and how inclusion is about embedding difference as standard. Authentic and holistic inclusion is the key to people feeling like they belong fully, and yet another vital component in psychological safety – and this safety and belonging are in turn fundamental for organisational performance.

George Dei, one of Canada’s foremost scholars on race and anti-racism studies, states that “inclusion is not bringing people into what already exists; it is making a new space, a better space for everyone.” Moving towards truly inclusive systems requires us to think about how our current practices may inadvertently be exclusionary, particularly of those least likely to self-advocate and to speak up. So many of our standard practices are anxiety provoking, for anyone – recruitment and cultures of overwork are two areas that frequently come up in my leadership coaching – but the impact is especially brutal for the marginalised.

As a leader, how do you reflect on your approach to inclusion? Are your practices designed to be affirming for those from the margins? For an in-depth foray into this I highly recommend a read of Ludmila Praslova’s groundbreaking inclusion framework as presented in The Canary Code – the analogy relates to the historic use of canaries in UK coal mines as living, breathing carbon monoxide detectors, now a modern metaphor of people who are particularly affected by dysfunctional organisational environments and injustices. The core principles of the Canary Code framework extend what works for neuroinclusion to supporting holistic belonging for all, creating the ideal conditions for psychological safety: workplace systems that are valid, flexible, transparent, trauma-informed, human-centric and talent-friendly.

I hope you’ve found this helpful – do share your thoughts if you have a moment.

Natalie Snodgrass

Quiet Space Ltd

- PSI quartiles are 1st: 14-61 PSI, 2nd: 61-76 PSI, 3rd: 76-86 PSI, 4th: 86-100 PSI. Benchmarks for the dimensions have been baselined through a 4-month trial PSI from 2665 Fearless Organization Scan respondents. ↩︎

- Here’s a great article on the interplay between trust and psychological safety, if you want to read more: https://psychsafety.com/the-difference-between-trust-and-psychological-safety/#:~:text=Trust%20is%20necessary%20for%20psychological%20safety%2C%20but%20not%20sufficient.,in%20a%20team%20are%20set. ↩︎

I posted the image above on my social media accounts a while ago and was amazed to find how much it resonated with people. Maybe you’re not tired, maybe you’re just doing too little of what makes you come alive. It’s a theme that has kept cropping up in my coaching sessions and in random conversations with people over these last couple of months, as well as something that has been particularly close to my heart this past year.

I posted the image above on my social media accounts a while ago and was amazed to find how much it resonated with people. Maybe you’re not tired, maybe you’re just doing too little of what makes you come alive. It’s a theme that has kept cropping up in my coaching sessions and in random conversations with people over these last couple of months, as well as something that has been particularly close to my heart this past year.