Responding to Change in a VUCA world

Greek philosophers are pretty good at pithy quotes. To illustrate, I give you this from Heraclitus of Ephesus: “Panta rhei”, or “everything flows”. Modern-day parlance has translated this into “the only constant in life is change”.

21st-century change has taken Heraclitus’ observation a step further: change these days isn’t simply a constant. It also isn’t linear, incremental or predictable. Even before the current pandemic we were in a period of social, geopolitical, environmental and technological volatility and disruption. You may have encountered the acronym VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous), originally coined by the U.S. Army in the 1990s to describe the post-Cold War world (and more widely adopted across the leadership literature post 9/11 to describe a work environment characterised by the turbulent and uncontrollable unknown). It may be the circles I’ve been moving in lately, but it does seem that as an easy acronym it’s now entering the general lexicon as it becomes more relevant than ever to all of us.

There are criticisms about the limitations of VUCA as a framework (e.g. cultural bias, ‘past its sell-by date’, convenient label for a challenging reality without adequate exploration of how we can respond to that reality, etc.), but rather than going off on a tangent I’m going to observe that there are some useful concepts that it offers us.

Change is volatile and complex. The changes we are encountering in our personal and professional lives are rapid, sudden and unstable. They’re becoming ever more dramatic, and moving at an exponential rate. In contrast to many of the complicated challenges you may have come up against in the past, complex problems don’t have logical solutions where an evidence-based approach and learned expertise are all you need. Instead, multiple interconnected variables interact in unpredictable ways and the relationship between cause and effect is blurred. We’re called upon to manage paradoxes and polarities, and if we’re looking for clarity and ‘right’ answers, we’re likely to be disappointed.

Change is uncertain and ambiguous. Changes are also unfolding in unanticipated ways – the context we live in is an evolving state of ambiguity. Like the iteration of fractals or a murmuration of starlings, you can’t predict how the system will change or what will emerge. Historical forecasts and past experiences are, increasingly, no predictor of the future, and planning is becoming an increasingly difficult challenge as the shape of things ahead becomes more and more uncertain. It can feel rather like an existential threat – many of us have a preference for safety and certainty, and when we can’t easily predict what’s going to happen, we have a tendency to predict hazard.

So, what to do? How do we make sense of complexity and our place in a volatile, uncertain and ambiguous world? How do we want to show up? Here are my thoughts on some of the ways we might respond, in both professional and personal contexts.

Control vs. curiosity: Standing in inquiry

When there is no blueprint to follow, trying to control the future is an approach destined to frustrate. You may be able to predict broad-brush behaviours, but specific outcomes for specific situations are unknowable. Past experiences, paradigms and dogmas are all ripe for scrutiny. Rather than a focus on control, therefore, we need to respond in a different way – by cultivating curiosity. The answers we seek will change in place and time, but a discipline of inquiry will be a stalwart essential in helping us navigate the way ahead.

What good questions can we ask? Here are some potential starters:

- In how many different ways can we look at the problem?

- What has thrown us off-course, and what can we learn from that?

- Are there any patterns? Exceptions?

- What is the most important challenge we need to focus on?

- What resources and influence are available to us?

- What values and guiding principles do we want our actions to align with?

You have come to the shore. There are no instructions. – Denise Levertov

Not Knowing: There may be no ‘right’ or clear answers

In the above context it’s also important to acknowledge and accept that there may be no ‘right’ or clear answers – the systems that we are part of are dynamic, and at any point in time there may be paradoxical tensions at play: short-term measures vs. long-term strategy; performance vs. wellbeing; the needs of the collective vs. the individual. This makes it critical that we are open to a diversity of views, helping us to expand our own perspective through constructive debate and dialogue.

Getting comfortable with being in a space of not knowing, and creating an environment in which we can inhabit that space with others, requires a few things of us. I think the following are particularly worth reflecting upon:

- No man is an island. It can be difficult to admit that you don’t have the answers, but there is strength in vulnerability. How can we stand in inquiry together with others so that new and diverse thinking can be encouraged to emerge, and collaborative solutions to new challenges can be co-created?

- We may not always be able to plan for a desired outcome, but we can nonetheless seek to develop in ways that allow us to seize the day when opportunity presents itself. What can we do right now to shore up our capacity for resilience, whether personal or organisational? At a personal level, how can we orient our thinking towards an attitude of optimism, self-efficacy and healthy risk management, and how can we develop our capacity for persistence and flexibility?

Experiment, fail

The curiosity that we need to encourage is all about an appetite for continual learning. Solutions to novel and complex challenges don’t come about through repeating what we’ve always done and reiterating what we already know – they need to emerge through seeking out new experiences and new knowledge and insight. Evidence-based methods need to be accompanied by an attitude to risk that involves encouraging experimentation and an agile, iterative approach: trying, failing, regrouping and learning, and trying again. Sometimes it also requires a leap of faith – jumping and not knowing where you’re going to land, but taking each step in line with your core values and principles, and trusting in the journey.

Traveller, there is no path. The path is made by walking. – Antonio Machado

Compassion and connection

At the core of everything is the person. Any approach we take needs to embrace both the rational and the human: the values, emotions, the way our social and cultural history can bind us to limiting horizons for action. In the face of threat and pressure it is exceedingly easy to find ourselves being harsh and critical of ourselves, or judgemental and intolerant of others.

Many of us find self-compassion a big ask. We may be able to show compassion to others, but then judge ourselves by a far harsher standard. Negative self-talk is common and perpetuates an unhelpful mindset. These are hard times, during which it can be hard to focus, see the bigger picture, and perform the way we may have been used to. These tough moments don’t need us to square up to them – they require us to be firm yet resolutely gentle with ourselves. I am dealing with a lot, and it’s ok not to be ok. What’s the best thing that I can do for myself right now that will help me get to where I need to be? Self-compassion is also vital in experimentation – we need to allow ourselves to fail.

That same compassionate-yet-firm approach also applies to the way we deal with others. When we’re stressed and there is no clear way forward it depletes our inner resources, which usually means we are much quicker to become irritated when other people don’t meet our expectations or frustrate our intent. Rather than reacting with intolerance, however, we can elect to respond with kindness, understanding and respect. Starting with kindness makes it far more possible to forge a connection through which we can jointly work to find solutions.

A discipline of inquiry, getting comfortable with not knowing, and a willingness to experiment can all take practice. I think compassion, though, calls upon something that is an integral part of our humanity; something that can be simple, straightforward and constant in the face of a volatile and complex reality. Henry James said: “Three things in human life are important. The first is to be kind. The second is to be kind. And the third is to be kind.” We are all in this together, and a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world is a little easier to deal with when we place compassion at the core of us.

– Written by Natalie Snodgrass, Quiet Space Ltd

I posted the image above on my social media accounts a while ago and was amazed to find how much it resonated with people. Maybe you’re not tired, maybe you’re just doing too little of what makes you come alive. It’s a theme that has kept cropping up in my coaching sessions and in random conversations with people over these last couple of months, as well as something that has been particularly close to my heart this past year.

I posted the image above on my social media accounts a while ago and was amazed to find how much it resonated with people. Maybe you’re not tired, maybe you’re just doing too little of what makes you come alive. It’s a theme that has kept cropping up in my coaching sessions and in random conversations with people over these last couple of months, as well as something that has been particularly close to my heart this past year.

©Roz Chast, The New Yorker

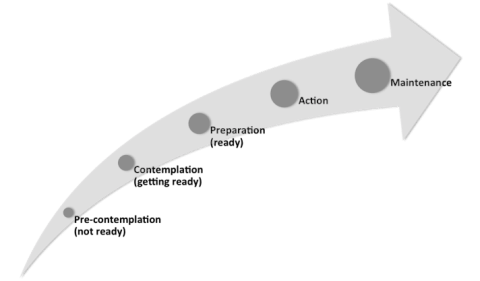

©Roz Chast, The New Yorker (The Transtheoretical Model of Change, Prochaska and DiClemente)

(The Transtheoretical Model of Change, Prochaska and DiClemente)